Peter Kotiuga

July 15, 2025

Peter Kotiuga discusses how having students learn the prosodic features of ancient Greek and Latin (e.g. syllable length, elision, and accentuation) early, as elements of pronunciation and independent of metrics, provides fresh opportunities to make lessons on meter more accessible, engaging, and discovery-driven.

Most lessons on the prosody of ancient Greek or Latin — that is, on the details of intonation and pronunciation — are reserved, intentionally or not, for lessons on meter. Some instructors of beginning Latin introduce students to macrons, but many do so only to help students disambiguate inflectional endings. The contrast between long and short vowels may be significant for a beginning Greek student, but again, mainly to help with learning accents. I know instructors who do more and others who leave all that for later. Beyond macrons and accentuation, topics such as long vs. short syllables, elision, and correption rarely enter the discussion before students begin deciphering metrical schemes. This approach introduces two problems in my view. The first is that a metrical introduction to prosody tells students that things like elision and correption are metrical phenomena when they are simply features of the spoken language. The second problem is that teaching prosody and meter at the same time is a heavy lift. Overwhelmed, many students blame meter for the exceptions and licenses of Greek and Latin prosody rather than seeing it for what it is: a playful, artful, and sometimes mystical use of language.

I would like to propose that we try introducing the prosody early on before framing it as the tool with which students can discover and derive the meter. That means spending more time with topics such as vowel length and elision, explicitly or not, in introductory courses and intermediate courses before meter is ever mentioned. I believe a prosody-first approach could not only reduce the burden of introducing students to meter, but it may even make prose rhythms more apparent and accessible to students. In other words, let’s not teach students to force the language into a given scheme with a list of rules and exceptions; let’s give students a firm foundation in the sounds and rhythms — the prosody — of Greek and Latin, which they can later use actively to discover meter for themselves.

A typical introduction to the dactylic hexameter, for instance, might go as follows. Six long “princeps” syllables (—) alternate with “biceps” elements (⏔) until the final, “indifferent” position (which is rhythmically long even if the final syllable is short and symbolized neither by anceps [×] nor by an optionally long or short position [⏒] but by a fermata, the unicode symbol for which few fonts support):

1— ⏔ | 2— ⏔ | 3— ⏔ | 4— ⏔ | 5— ⏔ | 6— —

The next lesson introduces long and short syllables, as opposed to long and short vowels, and it begins simply enough for both Greek and Latin: long syllables comprise long vowels, diphthongs, and short vowels followed by two or more consonant sounds; everything else is short. All that simplicity, however, goes out the window in the following lessons on elision (vowel loss due to vowel contact), correption (syllable shortening, whether by vowel contact or the ligature of consonant sounds), hiatus (a lack of vowel loss or shortening between vowels in contact), contraction, crasis, and synizesis (all forms of vowel mixing or loss due to contact).

What I want to emphasize is that nothing I discussed following the metrical scheme is strictly metrical. Both syllable length and vowel contact influence the sound of ancient Greek and Latin whether the words are in meter or not. So why not separate the lessons? Coach early students to over-articulate each consonant sound and to pronounce long vowels and diphthongs for twice as long as other vowels. For example, write the vowels on the board and clap once for “o,” twice for “ō.” As drummers say, “slow is fast” (that is, practice slow to play fast). Students who are taught syllable length and metrics at the same time tend to add stress to the long syllables as if following a qualitative meter. By developing the habit of over-articulating long vowels and consonant clusters early on, however, the meter largely comes through in recitation. Tap the rhythm if need be, but don’t stress it.

Sometimes our clean grammatical categories get in the way, too. Vowel contraction may seem distinct from crasis and synizesis, but the two are essentially the same, and both are shades of gray with elision and vowel correption. Is δὴ αὖτε –> δηὖτε all that different from ὁράω –> ὁρῶ for new Greek students? What about laudā-ō –> laudō vs. ille et –> ill’ et for a Latin student? If an instructor is already teaching students about vowel contraction and accentuation, why not model elision and correption while reading aloud as a class? (If “real-world” examples are needed, introduce your students to some Spanish or Italian; date yourself with “Despacito”: Muéstram[e]’ el camino que yo voy.) My suggestion is to find ways to raise students’ consciousness of vowel length and vowel contact as a feature of the language long before they see or think of a metrical scheme, to get students to practice elongating their long vowels, simplifying their short ones, luxuriating in long syllables, and curbing the elided and correpted ones, whether giving voice to prose or to poetry. Ancient orators avoided vowel contact and certain sequences of syllables. Why imply that only poets paid attention to syllable length and vowel contact?

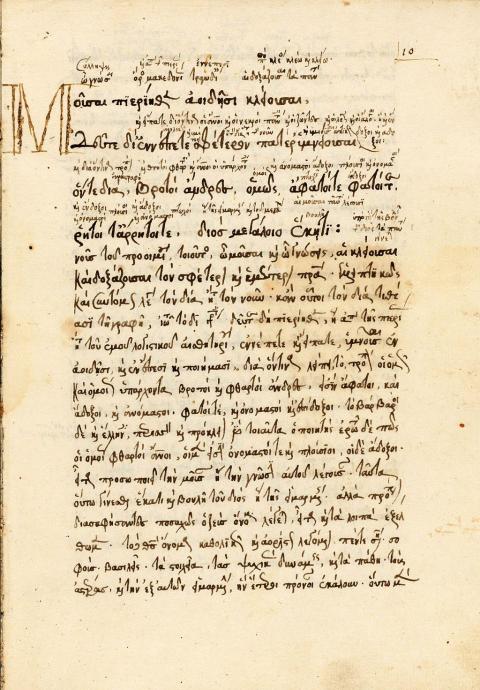

Teaching students the prosody before metrics also offers an opportunity to engage students in actively spotting the metrical scheme, to scaffold and “gamify” lessons in metrics. Call the lesson something like “Guess that Meter!” and, after practicing and reviewing the prosody with students, offer them a few verses and ask them to count the number of syllables or the number of beats (or “morae”) expressed in those syllables. See if students can find a common rhythmical denominator across those verses and can produce their own metrical scheme, discussing the rhythm of the verse both generally and in the assigned reading. The proems of the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the Aeneid are fairly straight forward despite a few complications, but those can be addressed with a word-bank or glossary (Πηληϊάδεω ends with synizesis; Lavinia has a consonantal “i”). By holding the metrical scheme back and using lessons in prosody as scaffolding, as “the tools” students need to detect the metrical structure for themselves, we can design new, active-learning lessons on metrics.

Let us also not forget that the syllables constitute only one aspect of verse rhythm. I will leave the specifics for a longer discussion, but there is no question that the word divisions, clause boundaries, and accentuation of Greek and of Latin contribute almost as much to the sounds and rhythm of the verse as the syllables themselves do. The interplay of ictus and accent is well known in Latin verse, and there is good evidence that the ancient Greek pitch accent effected percussive and melodic rhythms. Word divisions and clause boundaries, too, deserve more than the observation that in the hexameter, for instance, there is a caesura in the third foot of 99% of verses and often a division before the fifth foot. Word and clause boundaries occur with significantly different frequencies, but offering students statistics and a diagram of boundaries and bridges can quickly become overwhelming and abstract. Instead, why not let students discover these features for themselves? Assign them to tally up different sorts of divisions over some sample of verses and then have them calculate and interpret the trends for themselves.

Another way to approach word, phrase, and clause boundaries is in the context of teaching students to “chunk” phrasal units. In this case, one might offer students a poetic text formatted like prose and have them “chunk” it. Perhaps a group of students who read the text as prose will come up with different divisions than students who work with the text formatted in verse. Either way, this practice primes students to perceive the transition between smooth and rough rhythms and between balanced and unbalanced cola.

The prosody of the language was the prosody of the language whether an utterance was metrical or not. Taught early on and as a feature of pronunciation rather than of metrics, an emphasis on syllable length, vowel contact, accentuation, and word units offers students a more accurate and lively image of the rhythm and flow of these languages. Regardless of metrics, we ought to give priority to the sounds of the language when dealing with texts that were often composed for consumption by a listening audience, whether at a formal performance or in an intimate setting. And in the spirit of active learning, let’s challenge our students not just to learn that meter exists but to discover it for themselves and to put those new skills to work.

Authors