Nina Papathanasopoulou

November 2, 2023

The Ancient Worlds, Modern Communities initiative (AnWoMoCo), launched by the SCS in 2019 as the Classics Everywhere initiative, supports projects that seek to engage broader publics — individuals, groups, and communities — in critical discussion of and creative expression related to the ancient Mediterranean, the global reception of Greek and Roman culture, and the history of teaching and scholarship in the field of classical studies. As part of this initiative, the SCS has funded 168 projects, ranging from school programming to reading groups, prison programs, public talks, digital projects, and collaborations with artists in theater, opera, music, dance, and the visual arts. To date, it has funded projects in 33 states and 16 countries, including Canada, the U.K., Italy, Greece, Spain, Belgium, Ghana, Puerto Rico, Argentina, India, and Australia.

In this post, we focus on three projects that engage with the literature and history of the ancient Greek and Roman worlds. These projects explore issues of violence, suffering, gender, and race and try to make use of the past in order to better understand the present. They include a new film version of the humorous short epic The Battle Between the Frogs and the Mice, produced in the UK; Greek Love, a project based in Australia that makes use of Graeco-Roman antiquity to explore queerness; and a new adaptation of Medea in Pennsylvania that explores both Black issues and the cultural significance of social media.

The Battle Between the Frogs and the Mice

With the support of the SCS, UK-based director and performer Hannah Barrie embarked on a project to create a short film of the ancient epic parody The Battle Between the Frogs and Mice. Having had recent training in puppetry at the Curious School of Puppetry in London, Barrie approached the text with an eye to turning it into a puppet show that she would then film. She used A. E. Stallings’ translation and Joel Christensen’s commentary, both of which inspired the creation of the project. She and her team then worked with the Out of Chaos theatre company, who invited them to showcase the film as part of their Reading Greek Tragedy Online project with the Center for Hellenic Studies and the Kosmos Society.

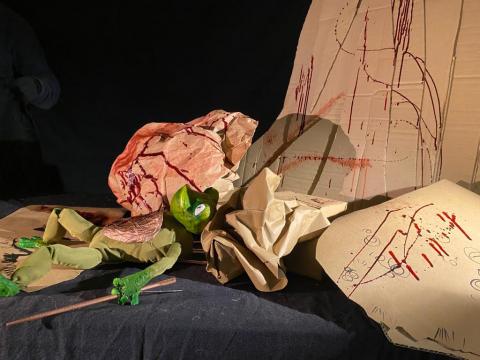

Inspired by the foreword to Stallings’ translation, Barrie decided to frame the epic with a mouse writing the tale in the Library at Alexandria. Many of the puppets and sets were created from reused materials: recycled foam, plastic tubing from household items, old toys, plastic balls, packing wool, and rubber bands. They filmed over two days, transforming her living room into a mini studio. Barrie worked with puppeteers Eoin Lynch and Aysil Aksehirli to bring the puppets to life, and with Rene Thornton, Jr., Natasha Magigi, and Sarah Finigan, who offered their voices to the characters. They spliced together some scenes and used filmed battle footage overlaid on their own puppet battle sequences to heighten the action and the bloodiness and destruction of the battle.

Barrie comments on her approach to the poem and her experience making the film:

Although the poem is sometimes considered to be quite light and “just for children,” our experience in making it was that it is incredibly moving. The loss of animal life made us think about the loss of human life in war, and for me, the needlessness of it all was particularly striking. With puppets, your imaginations fill in the story — and so the death of Crumbsnatcher is all the more moving, the deceit of Pufferthroat all the more enraging, and the resulting bloody battle all the more shocking. One thinks about the lies told by those in power to achieve what they want and how it is the ordinary people (or animals!) that suffer the most.

The episode aired on May 23 and was followed by a discussion with Stallings and Christensen on the process for making it all happen. The video will remain online as part of the digital archive of performances created by the series. Barrie and her team are also exploring how they might transform this into a live theater show, possibly incorporating other animal stories from antiquity. To this end, they will be organizing two workshops in September/October in collaboration with St. Andrew’s in Hove, a local primary school. They have arranged to work with about 60 students aged 10–11 and plan to focus on aspects of storytelling, adaptation, and puppetry. These workshops will be inspired by the Battle Between the Frogs and Mice but will also extend to incorporate other ancient stories.

Greek Love at the Hellenic Museum in Melbourne, Australia

Greek Love is an ongoing project organized by the Hellenic Museum in Melbourne, Australia, which responds to the growing interest in engaging with histories that resonate with queer being and knowing. The project creates opportunities for informal discussions of sexuality, gender studies, and queer theory through historical and contemporary lenses, in a way that is accessible for the wider public and highlights the role cultural institutions can play in supporting marginalized communities. The project team comments:

Graeco-Roman myths and histories have been popular mediums through which same-sex relationships, gender exploration, and human diversity have been portrayed. Today, modern LGBTQ+ communities are approaching these myths and histories from unique perspectives, challenging dominant narratives and dismantling the notion that there is, or ever was, a normative way of being.

The project is led by Tobias Fulton, a queer Ph.D. candidate at the University of Newcastle in Australia, and an Education and Public Programming Officer at the Hellenic Museum. With the support of the Ancient Worlds, Modern Communities grant, the Hellenic Museum hosted its latest Greek Love event on June 9, in celebration of the opening of Greek Love: Outside the Lines, a new exhibition in collaboration with queer Australian artist Mayticks.

In Greek Love: Outside the Lines, a Hellenic Museum gallery has been transformed into a color-by-numbers mural. Throughout the artwork, Mayticks has merged contemporary LGBTQ+ themes with ancient icons including Sappho, Achilles and Patroclus, the Roman emperor Elagabalus, and the Goddess Cybele and her Galli. Guests of the event were given the first chance to participate in the mural which, once complete, will remain on display for three months. In this way, Fulton noted, “the exhibition was designed to disengage from institutional Pride Month tokenism and create opportunities for co-creation and power sharing between institution, artist and visitor.”

For Lily Hawkins, Marketing and Communications Manager at the Hellenic Museum, the event was a critical success. 100 guests attended the sold-out evening of informal talks from four queer Australian classicists, historians, and academics, complete with an exhibition preview. Based on existing visitation and digital audience data, it is estimated that the project will be exposed to more than 100,000 viewers online and attract over 4,000 visitors.

According to Fulton, following the event, many LGBTQ+ identifying guests stated that Greek Love had been an affirming experience which made them feel “incredibly seen and heard.” In a post-event feedback survey, one guest disclosed that, as a queer Greek woman who had struggled finding acceptance from her culture, engaging with the queering of Greek histories and mythologies had been a healing experience. “Such feedback is not only incredibly moving but yields exciting prospects for future iterations of Greek Love,” Fulton comments.

Media/Medea

I am putting on the gorgon, the harpy, the crone, the vixen, the devourer goddess. I am the woman they made myth about. I am now Medea.”

James Ijames, Media/Medea

Under the initiative of Catherine Conybeare, Leslie Clark Professor in the Humanities at Bryn Mawr College, a brand new adaptation of Euripides’ Medea was presented in consecutive weeks at Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania, and the Community College of Philadelphia (CCP) this past April.

South Philly playwright James Ijames composed the play specifically for the two institutions. Ijames recently won a Pulitzer for his adaptation of Hamlet, Fat Ham. For his new play Media/Medea, he was even more creative. He set Media/Medea in a Black celebrity family. The parents’ marriage is exploding, the kids are in the middle of it, and the chorus are a group of their schoolmates who constantly comment on social media. The whole family is on display all the time.

As Conybeare explains, the performance of Media/Medea was the culmination of a year of collaborative programming between Bryn Mawr and CCP, “Greek Drama/Black Lives.” The project was designed to lift up both institutions and strengthen the connections between them after the disruptions and damage caused by COVID-19. Supported by a Sustaining Public Engagement Grant from the ACLS (with funding from the NEH), the project included talks, classes, and workshops, not least an interview with Ijames himself.

For Media/Medea, the cast was drawn half from Bryn Mawr, half from CCP. Over the course of a full semester, they rehearsed five days a week on alternate campuses — one week at Bryn Mawr, one at CCP. The production itself took place on both campuses. The entire set was moved down from Bryn Mawr to CCP in 24 hours of frantic work.

Support from Ancient Worlds, Modern Communities was used to transport half the cast each week some thirteen miles between the city of Philadelphia and the suburban campus of Bryn Mawr. This travel was essential as the terms of the principal grant specified that it could not be used for travel — and to make the collaboration fully reciprocal, they needed to involve both campuses equally.

According to Conybeare, the production was a triumph. On a practical level, inter-campus friendships were formed and inter-campus channels of communication developed or improved. A whole new pathway for transfer students from CCP to Bryn Mawr was developed. On an artistic level, students — both cast and crew — surpassed their own expectations. Excitement about the production spread across both campuses, and all seven performances were sold out. News spread beyond the campuses, and the production was written up in the Philadelphia Inquirer. As Conybeare comments, “above all it proved that, in the right hands, Greek drama can still question, provoke, delight, and draw communities together.”

Authors